This is Part 2 on Canada’s housing mania. I laid out the case for high prices in Part 1: Strong population growth, foreign investors, and high incomes on the demand side and a lack of building on the supply side are combining to create favorable fundamentals. When you add a benign outlook for interest rates, the argument for high prices looks strong.

And now, the case for a crash.

The Pandemic is ending

Start with the obvious: the Covid Pandemic. Two years ago, everyone suddenly wanted more space for their home offices and to manage their sanity during recurring lockdowns. By and large, people had more money to spend since governments provided far more in fiscal support than was lost in incomes. And with little to spend on, the savings rate jumped which padded potential down payments. By the start of 2021, 60,000 homes were selling every month1. New sellers were listing, but not nearly fast enough to meet demand. They may have thought waiting would raise the selling price, were spooked by having sick people in their homes, or simply looked around and realized if they sold, they would also need to move and there wasn’t much available. Whatever the cause, desperate buyers were forced to compete, the market tightened, and a frenzy began. As measured by the sales-to-new listings ratio, the market has never been this tilted in favour of sellers. What’s more, if you divide the total number of listings in the market by the pace of monthly sales, you can calculate the market’s inventory — i.e. how long it would take to sell every available house if no new ones were listed. Historically, inventory has averaged about 5 months. Currently its 6 weeks, the lowest ever recorded. This is the supply and demand balance currently reflected in prices. Does anyone think this can last?

The pandemic also disrupted migration trends within the country. While some people were standing in line to get into open houses in Toronto and Vancouver, tens of thousands of others were packing up and moving out. During the pandemic, rural Canada’s population jumped, and the Atlantic Provinces saw their fastest population growth in 50 years. As people moved from big cities to smaller places, competition increased and pushed prices up in every market in the country.

Now these factors are going into reverse. Government support has ended, the economy is reopening, and people are spending (causing inflation). In time, its reasonable to expect some of the shift in preference for larger homes will reverse too. Admittedly, this will be mitigated somewhat if work-from-home becomes a permanent fixture of white-collar life. There will likely be a rebound in supply too as people who put off moving or downsizing because of the pandemic do so. Rural areas and small cities may see some of their new arrivals trickle back to big cities, but even if they stay, new supply can be built in these places much faster and more easily than in cities which will ease prices. This is already happening: In 2021 housing starts in Canada’s small towns were up 31% compared with 2019.

Building is low, but it is rising

In Part 1 I argued that low building as a share of population growth is fundamental to high housing prices. In 2021 signs finally started to appear that new building is picking up. Housing starts jumped in 2021 to their highest level since the 1970s and those units will start entering the supply this year. Looking forward, building permits — the first step in the construction process — are also running at over 300,000 per year. While most of the new units coming down the pike are apartments and condos and not the increasingly scarce single-family homes, supply is supply. While I don’t think this level of new building is enough or of the right kind, it will help blunt the impact of strong population growth.

When interest rates go up, payments for new buyers will rise a lot

Then there are interest rates. The optimists can point to the fact that we still live in a world of low interest rates even if they’ll be going up over the next year or two. However, mortgages have increased dramatically as a share of the incomes which support them which increases the burden of any given increase in rates. The chart below shows the cost of a mortgage on a typical single-detached house as a share of the average income of a couple family with kids2. The spikes in the early 1980s and 1990s were caused first by rising prices and then by rising interest rates as the Bank of Canada tried to contain inflation. Those spikes were followed by house price corrections. Recently, rapid price growth has pushed up costs despite rates falling. If rates do rise, each 1 percentage point increase in mortgage rates will translate into an added $400 a month for a new buyer of the average detached house (more in big cities). Eventually as mortgages renew, it will raise costs for millions of existing homeowners. Some will become distressed and be forced to sell but more importantly it will discourage potential buyers, sapping demand.

And it isn’t just new buyers who are vulnerable. As house prices increased, Canadians have been taking wealth out of their homes in the form of Home Equity Lines of Credit (HELOCs) and mortgage refinancing. Famously, some of this is being used to gift tens of thousands of dollars to their children for down payments. Whatever the reason, interest payments need to be made on these balances and as interest rates rise that will become harder.

What if interest rates need to rise by more?

Economists expect interest rates to rise 1.5-2.0 percentage points over the next few years, but it may take more than that to contain inflation. The last time the Bank of Canada needed to wrestle inflation down in the early 1990s, interest rates rose by over 5 percentage points. A big, unexpected contraction of the money supply and rise in rates to contain inflation wouldn’t just raise people’s mortgage payments. It would discourage investment of all types, slowing economic growth and throwing people out of work. It would also raise government borrowing costs, which given high debt levels, would constrain government’s ability to provide stimulus in the event of a downturn. It may sound too dire to be plausible, but it’s exactly what happened in the 1990s.

Supposing we don’t get the severe outcome where rates rise a lot, we probably needn’t worry about interest rates because borrowers had to qualify under the stress test. Buyers proved they could carry their mortgages if rates rise, didn’t they? Well, maybe not. Anecdotes abound of widespread skirting of down payment and stress test rules. I doubt it’s all that common, but the true vulnerability of buyers in the most overheated markets may be higher than official data suggests.

Investors are exuberant

The market in 2022 has another worrying parallel to prior corrections: its increasingly driven by investors. According to the Bank of Canada, just over 20% of all buyers are now investors. In the last year they bought an estimated 134,000 homes, up 40% from before the Pandemic. This is a classic sign of an overheated market. Remember, unlike first-time or repeat buyers who live in their homes, investors are looking for profits and are therefore skittish and liable to exit the market when prices are falling.

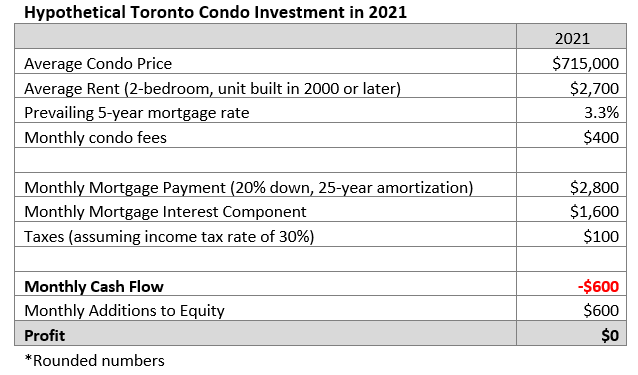

Crunching indicative numbers for these investors sends up further red flags. A hypothetical real estate investor buying the average Toronto condo in 2021 would probably collect just enough rent to cover the interest component of their mortgage plus condo fees and taxes. This would leave them cash-flow negative, and they would essentially be paying to build their own equity. This is a terrible investment! And I ignored property management, vacancy, insurance, and everything else which could easily make this math much worse. This only makes sense if prices continue to rise. And if an investment requires the price to rise beyond the fundamentals for it to make sense, that’s a bubble.

Increasingly Canadian buyers are showing signs of recency bias – anchoring on recent events as a prediction for the future. Canadian real estate has been bulletproof for so long that people underweight potential risks in their decision making. It is a common sentiment that buyers can rest easy because the government won’t let housing prices fall because the economy depends on it. It doesn’t help that most Canadian homebuyers were either not yet born or too young to remember the last downturn in 1990. When asked by the Bank of Canada how much they expected prices to rise in the coming year, Canadians said 4% in 2019. In 2021, after the biggest run up in history, they raised their estimate to 5.5%. That sure looks like irrational exuberance to me.

“If the reason that the price is high today is only because investors believe that the selling price will be high tomorrow – when “fundamental” factors do not seem to justify such a price – then a bubble exists”

— Joseph Stiglitz

“That is what a bubble is all about: buying for the future price increases rather than simply for the pleasure of occupying the home. And it is this motive that is thought to lend instability to bubbles, a tendency to crash when the investment motive weakens”

— Robert Shiller

The Millennials are Middle Aged Now

Finally, there is a demographic angle. Overall population growth may be strong, but the most motivated buyers are usually young people starting families. The last housing crash in the 1990s coincided with the end of the wave of Baby Boomers reaching their early 30s. They were having kids and wanted houses. Demand ramped up and supply couldn’t match, contributing to escalating prices through the 1980s. When the wave crested and fewer people were aging into that peak homebuying cohort, prices began to fall. The large Millennial generation will be the bulk of first-time buyers for some time, but as growth in the key age bracket slows and then turns negative it will remove some of the most motivated demand from the market.

The pandemic is causing unsustainably high demand from buyers desperate to move, its probably scaring potential sellers away from listing, interest rates are now too low and will soon rise, investors are crowding into the market with unrealistic price appreciation expectations, and the Millennials are all turning 30 and want extra bedrooms for their kids. The pedal is to the metal. Eventually these factors will abate. The pandemic will end, interest rates will rise, fewer new families will form, and investor sentiment will calm, and when it does, prices will fall. If interest rates rise by more than expected to quell inflation, prices could crash.

My Call

The factors supporting high prices are fundamental and slow-moving. Demand from population growth will continue to be strong and supply from new building and downsizing will continue to lag. I think those forces will dominate over the next five or ten years. However, prices in 2022 also reflect the effect of the pandemic on incomes and preferences, ultra-low interest rates, and exuberant investors. These factors are short term. I think they will end and when they do, prices will fall. Specifically, I think over the next 3 years, prices will fall 20% in Canada’s largest cities and 30% everywhere else. In the latter case, the places most at risk are those which received disproportionate pandemic migration including the Maritimes and Southern Ontario ex. GTA.

The fundamentals are most favorable in big cities. Population growth is strong, incomes are high, and supply is very constrained. Still, a simple model of the price families can afford to pay at somewhat higher interest rates suggests that homes are overvalued by 20-25%. That seems right to me. Intuitively, over the next few years interest rates will rise back to where they were in 2019, if not higher. Population growth will be stronger, but so will new building, keeping the degree of housing shortage broadly similar to pre-pandemic levels. Pandemic savings will unwind, preferences will normalize somewhat, and investor’s sentiment will turn, especially if the promised policy action on foreign buyers happens. In other words, the market could return to its pre-pandemic state — and prices. This implies a correction, but not a crash. The fundamental supply-demand mismatch will persist, keeping a single-family home out of reach for many people. To get a crash we’ll need central banks to raise interest rates by much more than expected. If that happens, homeowners will be squeezed by rising payments as people are losing their jobs and government spending is cut, causing a wave of distressed selling.

Outside of major cities, fundamentals are weaker in my view and therefore the likelihood of a bigger and more prolonged downturn is higher. Prices jumped as people moved out of major cities and brought city-sized buying power to smaller places. As I plan cover in a later post, much of that migration is a speeding up of existing migration trends that these places were temporarily unable to accommodate. Over time, new building will make housing more abundant and push down prices. Ageing Baby Boomers will prefer to live in their homes if they can, but that’s harder to do in small towns and rural areas so supply freed up by downsizing will probably be more substantial. It will also be available sooner. The median age in Canada’s big cities is 39, but in rural areas its 46.

Even if we get short-term gyrations for the reasons I’ve laid out, the basic unaffordability of housing will continue to plague much of the country until policymakers take steps to change the basic balance of supply and demand. The balance supporting high prices was largely caused by policy and it will take policy to unwind it. I’m not holding my breath.

On a seasonally adjusted basis

Using the price of a benchmark single-detached house, 5-year fixed mortgage rate, 25-year amortization and 20% down payment

This is a very well written and comprehensive series, thanks for your work here. I live in the Moncton area and the way that prices have ballooned & supply has bottomed out is really concerning. Our current municipal and provincial governments have welcomed this volatility as they are singularly focused on the increased property value as a sign of economic health and vitality. There is no discussion of the potential downsides or policy implementation to address a correction. Many who rent have been evicted so landlords can renovate property to flip back into the market. I also suspect that significant correction or crash would impact the region very negatively. We have not prepared.

Thanks again, I look forward to reading more of your analysis!

Wrong