Is Canada’s Housing Market in a Bubble? Part 1

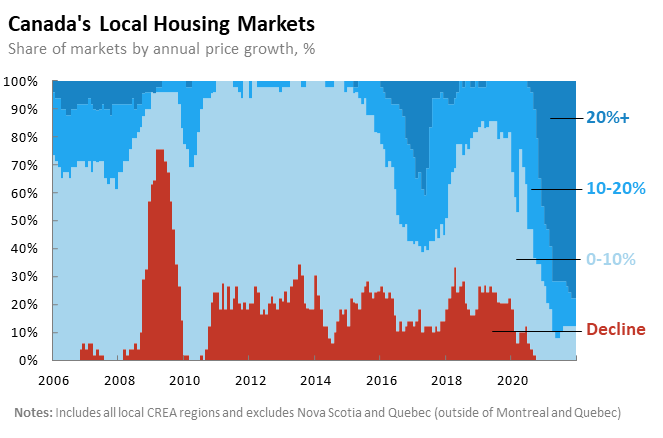

Canada is in the grip of housing mania. Across the country prices rose 18% in 2021, the fastest rate on record. High prices are nothing new to Toronto and Vancouver, which long ago priced most families out of single-family homes, but for the rest of the country it’s been a shock. Before the pandemic, many Torontonians and Vancouverites looking to buy had to drive ‘til they qualified – often to a far-flung suburb. Now you’d have to drive much further than that. At the end of 2021, three quarters of Canadian housing markets marked year-over-year price increases of over 20%. The market is “wild ”, “torrid”, and “stratospheric”. Since the start of the pandemic, Canadian homeowners have seen their housing wealth increase by over 500 billion dollars.

Comparing our circumstances against the United States’ recent past suggests cause for alarm. The U.S. housing market peaked in 2006, sparked a financial crisis, and then, adjusted for inflation, declined by 36%. During that episode Canadian housing only hit a minor speedbump before rising steadily for 12 years and then accelerating wildly during the pandemic.

As prices ran up, housing started devouring the economy. Canada now pays its real estate agents almost as much as its doctors1, residential investment is half of all real investment in the economy, and over half of all economic growth in recent years has been due to housing in one way or another.

So where is this all going? Are Canada’s high house prices here to stay, or is there a correction coming? Perhaps surprisingly, I think you can make a decent argument both ways. I’ll lay out the case that high prices are fair here in Part 1 and in Part 2 I’ll make the case for a crash. I’ll give you my take at the end.

We aren’t building enough new housing

The price of houses – like the price of everything – is driven by supply and demand. And in Canada supply is highly constrained: we are not delivering enough new housing to meet population growth. Since 2016 and despite the pandemic, Canada’s population growth has averaged 435,000 per year driven by steadily increasing immigration targets and large net flows of temporary residents (international students). This is up from an average of 358,000 in the decade previously. As population growth picked up, not only was new housing construction flat, it shifted toward apartments and condos. From 2006 to 2016, 38% of completed homes in Canada were apartments and condos. From 2017 to 2021 it was 49%. The upshot is that the completion of all housing – but especially family-friendly housing – as a share of population growth is at its lowest level in at least 40 years.

Admittedly, low supply of new units seems inconsistent with record high investment in residential construction. The first thing to note is that a high and rising share of that investment is in renovations which improve the housing stock, but don’t materially add much to its total size. Second, the price of new housing construction has soared, so the number of units we can build for a given level of investment is lower. The cost to build a new single-detached house in a large Canadian city has increased by 50% in five years. High prices are partly due to supply constraints in the construction sector which is running flat out, but regulations and fees are burdensome too.

Even more fundamental to lack of supply is zoning. In Canada’s big cities, it can be devilishly hard to get approval to build. For example, much of suburban Toronto is in the “Yellow Belt”, a classification which bans everything other than single- and semi-detached homes and then imposes further restrictions on height and other things. This entrenches low density, forcing population growth into towers and sprawl. Even if you are allowed to (re)build, your neighbors will probably fight you, potentially causing years of frivolous delays. The added headache and costs associated with building are borne by developers who pass those prices on to buyers. It also creates disincentives to build the so-called missing middle: medium-density, family-friendly housing. If it takes time and huge sums of money to clear the hurdle to build in the first place, you had better make it worth your while by building a lot of units — i.e. a tower.

New supply is constrained by relatively low building, but supply is also provided by sellers, especially those who move out of high-demand areas or into smaller units. Here too, supply is falling due to a change in preferences or circumstances among seniors who want to stay in their homes. In 2016, 70% of elderly Canadians lived in single-family homes, up from 63% ten years prior2. When surveyed, Baby Boomers say they’d prefer to live in their homes if possible and there are lots of amenities to help facilitate this. Reverse mortgages, home equity lines of credit (HELOCs) drawn on massive equity, low property tax rates, and subsidized or government provided in-home care all make it easier for aging homeowners to stay put. Suburban Canada is increasingly full of greying empty nesters who don’t intend to go anywhere.

Interest rates are low and probably won’t rise much

Low supply and high demand causes high prices, but to be a little more specific, it means that buyers will bid up the size of their mortgage payments. The prices supported by payments are based on amortization lengths and interest rates. When people go to a bank to qualify for a mortgage what usually matters is how much they can afford to pay each month (in addition to their down payment and tolerance for risk). The price is, in a sense, incidental. Canadian buyers are forced to pass a mortgage stress test, qualifying for their mortgages at a higher rate than they can receive in the market. In theory, new buyers can weather interest rate increases of at least 2 percentage points on their mortgage rates before becoming imperiled.

The optimistic case is that mortgage rates probably won’t rise much beyond that. Economists at big banks are predicting between 1.5 and 2.0 percentage points of interest rate increases by the end of 2023. The Bank of Canada thinks that the current bout of inflation will be short-lived and that over the long run the appropriate level of interest rates will remain low. The current estimate of the neutral rate of interest – the level that will neither stimulate or hold back the economy – is about 2.25%. The Bank expects to raise rates toward the neutral level over the next few years and that further hikes won’t be necessary to contain inflation. With central banks at neutral, mortgage rates (which are a few points above the Bank of Canada’s overnight rate) would be close to the stress-test bar that Canadians are already clearing.

The government will not do anything to jeopardize home values

The most fundamental cause of high demand is immigration-fueled population growth which is a policy choice. The most fundamental cause of low supply is zoning which is also a policy choice. These choices are made by different levels of government. Federally, both the Liberal and Conservative parties favor high immigration targets and rapid population growth. Most municipal politicians favor protecting neighborhood character (NIMBYism). The resulting policy brew is both stable and good for house prices. During the last Federal election, the parties rolled housing plans which generally involved vague building plans in municipalities but no substantive change to the fundamentals. Indeed, the fundamentals are being made worse. The Liberals promised (but have not yet delivered) billions to build or ‘revitalize’ tens of thousands of homes per year and at the same time raised the immigration target by 60,000 annually. Last year, Liberal MP Adam Vaughan, speaking at a CMHC conference said, “we have to be very careful that whatever steps we take protect the investments Canadians have made in their homes”. Electorally this makes obvious sense. Over 60% of Canadians are homeowners. You aren’t going to win elections promising them policies which will make them poorer. The takeaway is that it’s very unlikely that we will see government policies aimed at materially lowering the price of homes.

Canadians are rich and foreign investors are plentiful

If rates don’t rise much there is reason to think people can carry their monster mortgages indefinitely. While many young Canadians are struggling, there are lots of Millennials with good jobs who are often married to someone with a good job too. For instance, there are currently 126,000 young couples3 earning over $250,000 a year. That’s twice as many as ten years ago. These people work long hours and are perfectly happy to spend a big share of their big incomes on housing. If Canada gets the promised reduction in daycare fees over the next several years, that will free up even more of their money to spend on housing.

Then there is the added demand from foreign investors. In 2019, foreign investors owned 4% of Vancouver’s real estate, including 14% of newly built condos. In Toronto the comparable figures were 3% and 8%. Foreign investors aren’t driving the market, but they are adding fuel to the fire. Looking ahead, as a larger and larger share of the world’s wealth is created and owned by people living in poor countries with uncertain legal regimes, there will be a steady demand by investors to get their money out and park it somewhere safe. The safe place of choice is real estate in rich countries shielded as it is by a strong rule of law. In Canada this is even more enticing because when you send your money to our houses, you can send your children to our universities and put them on the path to permanent residency. Barring a major asset-market crash in Emerging Markets or a policy change, foreign investors will continue to add demand to housing markets.

For perhaps the most succinct version of the long-run case for high prices, consider that the country’s population growth is tracking somewhere between Statscan’s ‘medium’ and ‘high’ growth scenarios which puts the population somewhere between 48 and 55 million by 2050. This is the second-fastest growth rate among large rich countries (behind Australia). The population of the GTA will almost certainly surpass the five boroughs of New York City by that time. Vancouver’s growth would probably be slower given geographic constraints, but still strong. Imagine what a detached house would be worth then.

That’s the case for high prices. Next, Part 2: the case for a crash.

Physicians are paid about 15% of all health spending which is close to the GDP share of real estate offices.

Census 2006 and 2016

The older member of the couple is between 25 and 44.

The only part I don't agree with, "Barring a major asset-market crash in Emerging Markets or a policy change, foreign investors will continue to add demand to housing markets."

In fact, when there is a crash or when volatility in EM is high, there will be more demand for safe assets, to hedge against home country volatility. From the interest of Canadian homebuyers, you would want EM to be stable and boring, so that EM investors have less need to send their money to Canada, overheating the market.

Great to see unbiased work and footnotes in an article!