During the Pandemic millions of white collar workers and their employers learned they were capable of working fully remotely. With big-city amenities shuttered, people started looking for more space. This desire showed up in big-city housing markets, but anecdotes quickly accumulated of people fleeing the cities en masse. The Pandemic had the potential to reconfigure Canadian migration patterns in a big way. We now have two years of data and far from a disruption, the Pandemic appears to have sped up existing trends. Canadians were always moving out of big cities, they are just doing it faster now.

Canada’s internal migration before the Pandemic

Before the Pandemic, the most important migration trend in Canada was people leaving the cores and suburbs of big cities for exurbs and lifestyle regions. An exurb is a region of low-density commuter towns close to a major city, but farther away than the suburbs. Brampton is a suburb of Toronto and Barrie is an exurb. Generally speaking, a lifestyle region1 is a place which attracts people principally for its amenities rather than its job market and is beyond the commuter shed of major cities. This includes Niagara and the Muskokas in Ontario, much of Vancouver Island and the Okanagan in British Columbia, and the hinterlands north of Montreal. Here is a map of the classifications I use throughout.

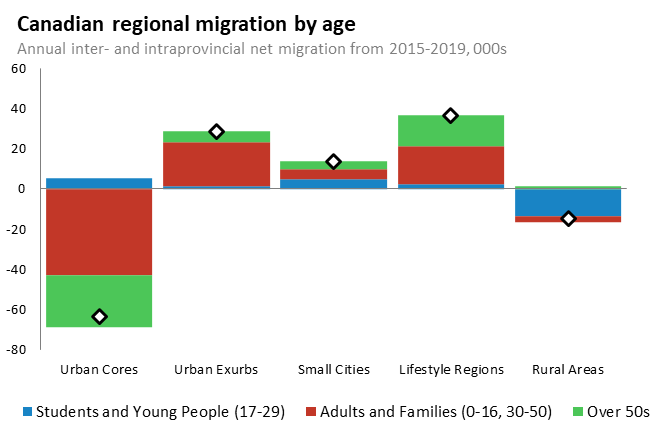

It might be surprising that big cities lose people to other parts of the country. Isn’t it common knowledge that cities pull people in for work? The fact is that big cities principally draw people from outside Canada – immigrants and foreign students. In 2019, almost 300,000 people2 from abroad settled in the GTA, Greater Vancouver, Montreal, Calgary, Winnipeg, or Ottawa. Among Canadian residents however, big cities and their suburbs lose tens of thousands more than they gain. Housing probably contributes to this as people “drive to qualify” — moving farther from the cores where prices are lower. This would explain why the biggest group moving to exurbs are middle-aged adults (aged 30-50) and their children (aged 0-16). Lifestyle regions are popular with families too but are particularly attractive to people over 50 who are near to, or already in, retirement and looking for a slower pace of life. Small cities gain across the age distribution and rural areas lose their young people.

The map below shows average annual migration for the five years leading up to the Pandemic. The urban cores of the biggest cities are blue, signaling net outflows, while exurban regions near them are red (signaling gains). Drive past those and you arrive at the lifestyle regions, also red. In Northern Alberta you can see the lingering impact of the 2015 oil bust3. When we think about the changes the Pandemic caused to migration patterns, we need to do it against this backdrop.

The Pandemic

The same map for the Pandemic years is below. You can tell at a glance that its similar. Migration from big cities — especially the GTA and Montreal — to traditional exurban and lifestyle communities sped up, and as it did it, it spread further out. The difference that everyone noticed, in 2020 anyway, was outright population decline in urban cores caused by the immigration stoppage. In 2021 the border reopened, and cities started growing again.

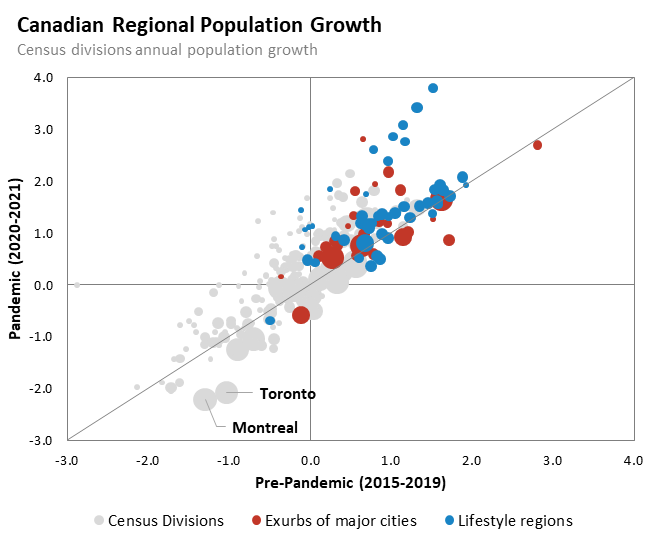

Here is another way to look at it. The chart below shows migration rates before and during the Pandemic in percentages per year rather than levels. Each bubble represents one of the regions in the maps above. The bigger the bubble, the larger the population. If a region is above the diagonal line, it grew faster during the Pandemic than before. Montreal and Toronto (below the line) are the big outliers that drove rising in-migration elsewhere. I’ve labeled the exurbs of big cities in red and lifestyle regions in blue. They were the fastest growing places in the country before the Pandemic, and their growth accelerated from there. Notice that there are very few bubbles in the top left or bottom right quadrants. Those are places where trends reversed during the pandemic (shifted from net outflow to net inflow, or the opposite). For the most part they are small regions in Quebec. Incidentally, the biggest losers are also generally unchanged, they are mostly rural areas on the Prairies or in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Boomtowns and Grey Towns

The Pandemic also magnified pre-existing migration patterns by age. Over the past two years, total migration to exurbs not only increased, it increased most among the largest cohort: middle-aged adults and their children. As white-collar workplaces reopen on hybrid schedules allowing at least occasional work from home, people may be calculating that they can endure longer commutes if it happens fewer times per week. The flow of older Canadians out of urban cores increased by a third and most of that increase went to lifestyle regions and rural areas. Of over 50s leaving big cities, a sizeable chunk left their province entirely and they disproportionately headed for rural areas. This looks to me like people moving back to their hometowns to retire. While this was only a tiny tributary in the flow out of big cities, for the small places they headed to it could be a torrent. In rural Nova Scotia for example, over half of net migration during the Pandemic was over 50s moving in from other provinces.

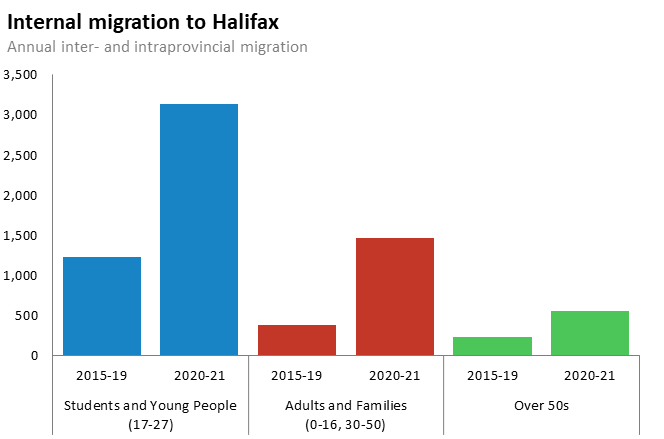

In aggregate, smaller cities had only minor changes to their migration patterns, but that conceals the fact that some are losing population like Regina or Windsor, some are gaining, and still others are booming. The posterchild for Pandemic boomtowns is Halifax where net migration more than doubled for all age groups. The relative youth of new arrivals4 has temporarily halted the city’s overall ageing and will pay economic dividends for decades — provided the newcomers stay. Yet even here, this is a case of pre-existing trends picking up: migration to Halifax was positive before the Pandemic as well. While few cities were as dramatic as Halifax, other cities seeing a rising influx of young people and families are Victoria and Hamilton.

Going forward

The Pandemic has not upended the patterns of Canadian migration, rather it has intensified them. If the new higher rates of outmigration persist, it could lead to big changes in Canada’s demography. For instance, normal rates of immigration and natural growth plus Pandemic-levels of internal migration would add the equivalent of another city of Guelph to exurban Toronto (i.e. past the Greenbelt) in just 10 years. The Okanagan would add 75,000 people and Halifax, 100,000, over the same period.

Of course, the Pandemic may be an aberration and when it ends we’ll return to prior trends or even see them reverse somewhat. However, if remote work becomes sufficiently widespread that white-collar workers feel safe to permanently leave big cities, things could accelerate further. And as newly remote workers on high incomes move farther and farther from big cities they will need amenities like homes, roads, and entire service economies. This will drive business and job creation, pulling still more people out. After a decade in which the majority of net new jobs were created in the biggest cities, a geographic rebalancing of the population and economy is tantalizing. If it happens, the beneficiaries will probably be already-popular exurbs and lifestyle regions. It is not all upside though. For instance, the unforeseen population boom in Halifax kicked off wild increases in house prices as new supply was unable to keep up. This was a windfall for sellers, but increasingly priced locals out of their own market.

Local and Provincial governments should begin planning now for new neighbourhoods which offer the amenities people are looking for (i.e. not just condos by the highways) along with supporting infrastructure and services. If managed well, these regions could offer a very high quality of life alternative to big city living for which there is clearly high demand.

Lifestyle regions are not rigorously defined. Here I am using places with commonly associated with desirable amenities and rural or small town living. They include much of Vancouver Island, the Interior of BC and the Okanagan, the Bruce Peninsula, Muskokas, and Niagara Peninsula, and the regions north and south of Montreal.

Immigrants, returning emigrants and net temporary migrants minus emigrants

The last time Canada had a shock to its internal migration was in 2015 when oil prices crashed. This ended a decade-long boom in Alberta which was absorbing a third of Canada’s internal migrants at the peak. Between 2000 and 2015, fully 8% of Atlantic Canada’s population moved to Alberta.

Average age of an internal migrant to Nova Scotia is 33.

Great read. If we aggregate to the provincial level, who gains and loses most from these changes?

Nice concise read. Now I understand why these price increases are happening here in Halifax. Previously thought this could only happen in much larger centers. Initially felt it was a great victory for homeowners but for most of us who don't want to leave, it is phyrric.